The Anarchist FAQ

Liberty is the mother, not the daugher, of order.

- What is anarchism?

- What does anarchism stand for?

- What is the essence of anarchism?

- Why do anarchists give priority to liberty?

- Are anarchists in favour of organisation?

- Do anarchists favour non-aggression?

- Are anarchists in favour of equality?

- Why is decentralization important?

- Why do anarchists argue for

self-ownership and self-liberation? - Do anarchists oppose hierarchy?

- Do anarchists oppose property?

- What sort of society do anarchists want?

- What will abolishing the State achieve?

- Do anarchists favour democracy or contract?

- Are anarchists individualist or collectivist?

- What about “human nature”?

- Do anarchists support terrorism?

- What ethical views do anarchists hold?

- Why are most anarchists atheists?

- What types of anarchism are there?

- Who are the major anarchist thinkers?

I. What is Anarchism?

Modern civilisation faces three potentially catastrophic crises:

- Organized mass murder (war) and the proliferation of WMDs - weapons of mass destruction.

- Organized plunder of society - the theft of people's wealth by taxation, tolls, licensure, fiat currency, etc.

- Environmental destruction and pollution of the planet’s ecosystems on which life depends.

- Social breakdown - rising rates of crime, violence, poverty, homelessness, disease, etc. caused by I - III.

Anarchism offers a unified and coherent way of making sense of these crises, by tracing them to a common source. The root problem is the belief in the principle of political authority, a belief which underlies the major institutions of most “civilised” societies, whether they have government-controlled capitalist, socialist, or mixed economies.

Anarchist analysis starts from the fact that all of our governmental institutions are a form of rulership, such as central governments ("States"), government bureaucracies, armies, cartel enforcement agencies (euphemized as regulatory agencies), crony corporations, political parties, religious organisations, NGOs, universities, and so on. Anarchist theory then goes on to show how the authoritarian relations inherent in compulsory government adversely affects individuals, their society, and their culture. In the first part of this FAQ (sections I to IV) we will present the anarchist analysis of State authority and its negative effects in greater detail.

It should not be thought, however, that anarchism is only a critique of modern civilisation, just “negative” or “destructive.” It is also a proposal for a free society. Emma Goldman expressed what might be called the “anarchist question” as follows: “The problem that confronts us today … is how to be one’s self and yet in oneness with others, to feel deeply with all human beings and still retain one’s own characteristic qualities.” [Red Emma Speaks, pp. 158–159] In other words, how can we create a society in which the potential for each individual is realised but not at the expense of others, that is, without aggressing against our fellow man?

In order to achieve this, anarchists envision a society in which, instead of being controlled “from the top down” through structures of centralised violence-power, the affairs of humanity will, to quote Benjamin Tucker, “be managed by individuals or voluntary associations.” [Anarchist Reader, p. 149] Sections V and VI of this FAQ describes visions and proposals for organising society in this way.

This FAQ is not the final word on anarchism. Some anarchists will disagree with much that is written here, but this is to be expected when people think for themselves. All we wish to do is indicate the basic ideas of anarchism and give our analysis of certain topics based on how we understand and apply these ideas. We are sure, however, that all anarchists will agree with the core idea of opposition to compulsory government, the State, even if they may disagree with particulars here and there.

If we look at the black record of mass murder, exploitation, and tyranny levied on society by governments over the ages, we need not be loath to abandon the Leviathan State and … try freedom. — Murray Rothbard, For a New Liberty

I.A - What is anarchism?

Anarchism is a political theory which aims to create anarchy, “the absence of a master, of a sovereign.” [P-J Proudhon, What is Property, p. 264] In other words, anarchism is a political theory which aims to create a society within which individuals freely cooperate together as equals. Anarchism opposes all forms of government control, be it control by president or dictator or legislator or majority, as harmful to the individual and his liberty.

“Anarchism” and “anarchy” are among the most misrepresented ideas in political theory. Generally, the words are used to mean “chaos” or “without order,” and so, by implication, anarchists desire social chaos and a return to the “laws of the jungle.” Lawyers are prone to this view, since Blackstone used "anarchy" in this manner. However, Pierre Proudhon took this pejorative term and embraced it, giving "anarchy" its political meaning of "no compulsory government." This process of embracing a curse word is not without historical parallel. The words "queer" and "capitalism" were also adopted by targets of derision and transformed into a positive term.

Also, there is a clear propaganda interest for rulers wanting to retain power to disparage new ideas. In countries with monarchy, the words “republic” or “democracy” have been used precisely like “anarchy,” to imply disorder and confusion. Those with a vested interest in preserving the status quo will obviously wish to imply that opposition to the current system cannot work in practice, and that a new form of society will only lead to chaos. Or, as Errico Malatesta expresses it:

Since it was thought that government was necessary and that without government there could only be disorder and confusion, it was natural and logical that anarchy, which means absence of government, should sound like absence of order.” — Anarchy, p. 16

Benjamin Tucker (1854-1939)

Anarchists want to change this “common-sense” idea of anarchy, so people will see that government and all other aggression-based relationships are both harmful and unnecessary.

Aggression is simply another name for government. Aggression, invasion, government, are interconvertible terms. The essence of government is control, or the attempt to control. He who attempts to control another is a governor, an aggressor, an invader; and the nature of such invasion is not changed, whether it is made by one man upon another man, after the manner of the ordinary criminal, or by one man upon all other men, after the manner of an absolute monarch, or by all other men upon one man, after the manner of a modern democracy. — Benjamin Tucker, The Individual, Society, and the State.

I.A.1 - What does “anarchy” mean?

The word “anarchy” is from the Greek, prefix an (or a), meaning “not,” “the want of,” “the absence of,” or “the lack of”, plus archos, meaning “a ruler,” “chief,” “person in charge,” or “authority.” Or, as Peter Kropotkin put it, Anarchy comes from the Greek words meaning “contrary to authority.” ["Anarchism," Encyclopedia Britannica (1910)]

Anarchy is a word that comes from the Greek, and signifies, strictly speaking, "without government": the state of a people without any constituted authority.

— Errico Malatesta, Anarchy: a pamphlet.Anarchism means first and foremost freedom from all government.

— Johann Most, The Social Monster (1890)Anarchism means no government, but it does not mean no laws and no coercion. This may seem paradoxical, but the paradox vanishes when the Anarchist definition of government is kept in view. Anarchists oppose government, not because they disbelieve in punishment of crime and resistance to aggression, but because they disbelieve in compulsory protection. Protection and taxation without consent is itself invasion; hence Anarchism favors a system of voluntary taxation and protection.

— Victor Yarros, Our Revolution: Essays and Interpretations p.80)

The Greek words anarchos and anarchia mean “having no government” or “being without a government.” “An-archy” means “without a ruler,” or more generally, “without political authority,” and it is in this sense that anarchists have used the word.

I.A.2 - What does “anarchism” mean?

Peter Kropotkin defined "anarchism" in the Encyclopedia Britannica (1910) as follows:

Anarchism [is] the name given to a principle or theory of life and conduct under which society is conceived without government - harmony in such a society being obtained, not by submission to law, or by obedience to any authority, but by free agreements concluded between the various groups, territorial and professional, freely constituted for the sake of production and consumption, as also for the satisfaction of the infinite variety of needs and aspirations of a civilized being.

For anarchists, anarchy means “not necessarily absence of order, as is generally supposed, but an absence of rule.” [Benjamin Tucker, Instead of a Book, p. 13] Tucker warned against adding other criteria, such as socialism, to "plumb-line" anarchist anti-statism.

A Socialist may or may not be an Anarchist, and an Anarchist may or may not be a Socialist. Relaxing scientific exactness, it may be said, briefly and broadly, that Socialism is a battle with usury and that Anarchism is a battle with authority. The two armies — Socialism and Anarchism — are neither coextensive nor exclusive; but they overlap. — [Benjamin Tucker, “Armies that Overlap”, p. 139]

Anarchism as such is purely anti-government or anti-state. Anarchism is not a movement against hierarchy, nor for or against any form of property. Why? Because people are self-owned, and have a right to live for their own lives. Anarchists are, by definition, anti-state; and principled anti-statism is a sufficient condition for someone to be an anarchist. Anarchists can and do oppose various other wrongs and injustices, but as anarchists we oppose only the state. In this case, the dictionary definition is quite accurate.

Anarchism - The theory or doctrine that all forms of government are oppressive and undesirable and should be abolished.

The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Third Edition

To summarize, anarchy does not mean chaos, nor do anarchists seek to create chaos or disorder. Instead, we wish to create a society based upon individual freedom and voluntary cooperation. In other words, we want order based on voluntary consent and contract, not disorder imposed from the top down. Such a society would be a true anarchy, a society without rulers.

I.A.3 - What other names does anarchism have?

Many anarchists, seeing the negative nature of the definition of “anarchism,” have used other terms to emphasise the inherently positive and constructive aspect of their ideas. The most common terms used are “libertarianism,” “voluntaryism,” “agorism,” and “panarchism.” For anarchists, voluntaryism, agorism, panarchism, and anarchism are virtually interchangeable.

There are some technical differences. Voluntaryism emphasizes the NAP, the non-aggression principle. While most anarchists are against aggression and take this approach, there are a few, such as Stirnirite egoists, who do not. Similarly, agorism is more precisely an anarchist strategy, the "counter-economic" way to work toward anarchy.

Another closely related term is "libertarian." Libertarianism means favoring a less authoritarian State, so anarchists are radical libertarians. While more mainstream libertarians want less government, anarchists want no government at all. Libertarians who are not anarchist are called "minarchist," since they favor a minimal state.

I.A.4 - Are anarchists socialists?

Not necessarily. As we saw earlier, Benjamin Tucker made this quite clear when he wrote,

A Socialist may or may not be an Anarchist, and an Anarchist may or may not be a Socialist. … Socialism is a battle with usury and Anarchism is a battle with authority.

However, anarchism is against corporatism - the collusion of State and favored special interests. This is because this crony "capitalism" is based upon special favors bestowed by rulers, resulting in oppression and plunder (see sections B and C). We must stress here that anarchists are opposed to all economic forms which are based on government domination, including feudalism, Soviet-style “socialism," slavery, and so on. We concentrate on corporatism and mixed economies because that is what is dominating the world just now. Note that some people use "capitalism" when they mean "corporatism" or statist capitalism. Anarchism is totally compatible with free market capitalism, laissez faire with zero government intervention.

In the 19th century even Individualists like Benjamin Tucker, along with more socialist anarchists like Proudhon and Bakunin proclaimed themselves “socialists.” They did so because at that time "socialism" meant simply oppostion to corporatism. "Capitalism" was a pejorative, and meant "corporatism" back then, too. Thus, today's modern anarcho-capitalism would have been called "stigmergic socialism" or some such in the 19th century!

European anarchism developed in constant opposition to the ideas of Marxism, social democracy and Leninism. Long before Lenin rose to power, Mikhail Bakunin warned the followers of Marx against the “Red bureaucracy” that would institute “the worst of all despotic governments” if Marx’s state-socialist ideas were ever implemented. Indeed, the works of Stirner, Proudhon and especially Bakunin all predict the horror of statist socialism with great accuracy. In addition, the anarchists were among the first and most vocal critics and opposition to the Bolshevik regime in Russia.

I.A.5 - Where does anarchism come from?

There were many precursors, but modern anarchism began with Josiah Warren in the U.S. and Pierre Proudhon in France. Both of these men, unknown to each other, were mutualist in their economics. It is interesting that neither anarcho-socialism nor anarcho-capitalism were known yet. Mutualism, being "middle of the road" in some sense, seeded both the individualist strain which later became anarcho-capitalism, geo-anarchism, and mutualism, as well as the socialist strain which became anarcho-communism and anarcho-syndicalism.

Josiah Warren

Laws and governments defeat their object. Their professed object is the security and good order of society. But the moment that any such power is erected over one's person or property, that moment he feels insecure and sees that his greatest chance of security is in getting possession of the governing power - in governing, rather than being governed. …

Strife for the attainment of this power, has in all ages up to the present hour produced more confusion, destruction of life and property, and more crimes and intense misery than all other causes put together.

I venture the assertion that the establishing of such powers has been the greatest error of mankind, and that society never will enjoy peace or security until it has done with these barbarisms and acknowledges the inalienable right of every individual to the sovereignty of their own person, time, and property.

— Josiah Warren, The Peaceful Revolutionist, 1833, vol. 1, no. 4

Like the Old World anarchist movement in general, the Makhnovists were a mass movement of working class people resisting the forces of authority in the Ukraine from 1917 to 1921. As Peter Marshall notes “anarchism … has traditionally found its chief supporters amongst workers and peasants.” [Demanding the Impossible, p. 652]

Anarchism was created in, and by, the struggle of the oppressed for freedom, according to some. For Kropotkin, for example, “Anarchism … originated in everyday struggles” and “the Anarchist movement was renewed each time it received an impression from some great practical lesson: it derived its origin from the teachings of life itself.” [Evolution and Environment, p. 58 and p. 57] For Proudhon, “the proof” of his mutualist ideas lay in the “current practice, revolutionary practice” of “those labour associations … which have spontaneously … been formed in Paris and Lyon … [show that the] organisation of credit and organisation of labour amount to one and the same.” [Daniel Guerin, No Gods, No Masters, vol. 1, pp. 59–60]

So anarchistic tendencies and organisations in society have existed long before Warren wrote "The Peaceful Revolutionist" in 1833 or Proudhon put pen to paper in 1840 and declared himself an anarchist. While anarchism, as a specific political theory, was born in the industrial revolution, anarchist writers have analysed history for libertarian tendencies. Kropotkin argued, for example, that “from all times there have been Anarchists and Statists.” [Op. Cit., p. 16] In Mutual Aid (and elsewhere) Kropotkin analysed the libertarian aspects of previous societies and noted those that successfully implemented (to some degree) anarchist organisation or aspects of anarchism. He recognised this tendency of actual examples of anarchistic ideas to predate the creation of the “official” anarchist movement and argued that:

From the remotest, stone-age antiquity, men [and women] have realised the evils that resulted from letting some of them acquire personal authority… Consequently they developed in the primitive clan, the village community, the medieval guild … and finally in the free medieval city, such institutions as enabled them to resist the encroachments upon their life and fortunes both of those strangers who conquered them, and those clansmen of their own who endeavoured to establish their personal authority.

— [Kropotkin, Modern Science and Anarchism, pp. 158–9]

James C. Scott also wrote about anarchist technologies and cultural strategies in Zomia, the anarchistic mountain regions of Southeast Asia, contrasted with the lowland rice paddy States.

Not so very long ago, however, such self-governing peoples were the majority of humankind. Today, they are seen from the valley kingdoms as “our living ancestors,” “what we were like before we discovered wet-rice cultivation, Buddhism and civilization.” on the contrary, I argue that hill peoples are best understood as runaway, fugitive, maroon communities who have, over the course of two millennia, been fleeing the oppressions of state-making projects in the valleys - slavery, conscription, taxes, corvée labor, epidemics, and warfare.

— James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia.

In other words, precursors of anarchism have been around since ancient times. Even Lao Tzu has been cited as a proto-anarchist, with poetry like the following;

The more laws and restrictions there are,

The poorer people become.

The sharper men’s weapons

The more trouble in the land.

The more ingenious and clever men are,

The more strange things happen.

The more rules and regulations,

The more thieves and robbers.

Therefore the sage says:

I take no action and people are reformed.

I enjoy peace and people become honest.

I do nothing and the people become rich.

I have no desires and people return to the good and simple life.

I.B - What does anarchism stand for?

These words by Percy Bysshe Shelley gives an idea of what anarchism stands for in practice and what ideals drive it:

The man

Of virtuous soul commands not, nor obeys:

Power, like a desolating pestilence,

Pollutes whate’er it touches, and obedience,

Bane of all genius, virtue, freedom, truth,

Makes slaves of men, and, of the human frame,

A mechanised automaton.

As Shelley’s lines suggest, anarchists place a high priority on liberty, desiring it both for themselves and others. They also consider individuality - that which makes one a unique person - to be a most important aspect of humanity. They recognise, however, that individuality does not exist in a vacuum but has a social component. Outside of society, individuality is generally stifled, since one needs other people and a harmonious division of labor for people to develop, prosper, and grow.

Anarchism is a complete denial of all political authority. As philosopher Michael Huemer wrote in The Problem of Political Authority:

Authority, then, has two aspects:Political legitimacy: the right, on the part of a government, to make certain sorts of laws and enforce them by coercion against the members of its society – in short, the right to rule.

Political obligation: the obligation on the part of citizens to obey their government, even in circumstances in which one would not be obligated to obey similar commands issued by a nongovernmental agent.

If a government has ‘authority’, then both (i) and (ii) exist: the government has the right to rule, and the citizens have the obligation to obey.

Liberty is essential for the full flowering of human intelligence, creativity, and dignity. To be dominated by another is to be denied the chance to think and act for oneself, which is the only way to grow and develop one’s individuality. Domination also stifles innovation and personal responsibility, leading to conformity and mediocrity. Thus a society that allows the growth and flowering of individuality will necessarily be based on voluntary association, not coercion and authority. To quote Proudhon, “All associated and all free.” Or, as Luigi Galleani puts it, anarchism is “the autonomy of the individual within the freedom of association” [The End of Anarchism?, p. 35] (See further section I.B.2 — Why do anarchists give priority to liberty?).

A stateless society will be the creation of human beings, not some deity or transcendental principle, since “nothing ever arranges itself, least of all in human relations. It is men who do the arranging, and they do it according to their attitudes and understanding of things.” [Alexander Berkman, What is Anarchism?, p. 185] Anarchism bases itself upon the power of ideas and the ability of people to act and transform their lives based on what they consider to be right. In other words, liberty.

I.B.1 - What is the essence of anarchism?

As we have seen, “an-archy” means “without rulers” or “without political authority.” Anarchists are not against authorities in the sense of experts who are particularly knowledgeable, skilful, or wise, though obviously such authorities should have no power to force others to follow their recommendations. In a nutshell, then, anarchism is anti-authoritarianism.

If the State, then, is a vast engine of institutionalized crime and aggression, the "organization of the political means" to wealth, then this means that the State is a criminal organization … It means, for example, that no one is morally required to obey the State … the State cannot possess any just property. This means that it cannot be unjust or immoral to fail to pay taxes to the State, to appropriate the property of the State (which is in the hands of aggressors), to refuse to obey State orders, or to break contracts with the State (since it cannot be unjust to break contracts with criminals). Morally, from the point of view of proper political philosophy, "stealing" from the State, for example, is removing property from criminal hands, is, in a sense, "homesteading" property, except that instead of homesteading unused land, the person is removing property from the criminal sector of society - a positive good. — Murray Rothbard, The Ethics of Liberty, ch. 24.

In other words, the essence of anarchism - to express it positively - is free cooperation between moral equals which respects their liberty and property.

The abolition of this mutual influence would be death. And when we advocate the freedom of the masses, we are by no means suggesting the abolition of any of the natural influences that individuals or groups of individuals exert on them. What we want is the abolition of influences which are artificial, privileged, legal, official.” — [quoted by Malatesta, Anarchy, p. 51]

One of “the grand truths of Anarchism” is that “to be really free is to allow each one to live their lives in their own way as long as each allows all to do the same.” This is why anarchists fight for a society which respects individuals and their freedom. Anarchists “believe in peace at any price — except at the price of liberty.” [Lucy Parsons, Liberty, Equality & Solidarity, p. 103, p. 131, p. 103 and p. 134]

Anarchists do not want to give others power over themselves, the power to tell them what to do under the threat of punishment if they do not obey. Perhaps non-anarchists, rather than be puzzled why anarchists are anarchists, would be better off asking what it says about themselves that they feel this attitude needs any sort of explanation.

I.B.2 - Why do anarchists give priority to liberty?

An anarchist can be regarded, in Bakunin’s words, as a “fanatic lover of freedom, considering it as the unique environment within which the intelligence, dignity and happiness of mankind can develop and increase.” [Michael Bakunin: Selected Writings, p. 196] Because human beings are thinking creatures, to deny them liberty is to deny them the opportunity to think for themselves, which is to deny their very existence as humans. For anarchists, freedom is a product of our humanity, because:

Emma Goldman (1869-1940)

“The very fact… that a person has a consciousness of self, of being different from others, creates a desire to act freely. The craving for liberty and self-expression is a very fundamental and dominant trait.” [Emma Goldman, Red Emma Speaks, p. 439]

For this reason, anarchism “proposes to rescue the self-respect and independence of the individual from all restraint and invasion by authority. Only in freedom can man grow to his full stature. Only in freedom will he learn to think and move, and give the very best of himself. Only in freedom will he realise the true force of the social bonds which tie men together, and which are the true foundations of a normal social life.” [Op. Cit., pp. 72–3]

Thus, for anarchists, freedom is basically individuals pursuing their own good in their own way. Doing so calls forth the activity and power of individuals as they make decisions for and about themselves and their lives. Only liberty can ensure individual development and diversity. This is because when individuals govern themselves and make their own decisions they have to exercise their minds and this can have no other effect than expanding and stimulating the individuals involved. As Malatesta put it, “[f]or people to become educated to freedom and the management of their own interests, they must be left to act for themselves, to feel responsibility for their own actions in the good or bad that comes from them. They’d make mistakes, but they’d understand from the consequences where they’d gone wrong and try out new ways.” [Fra Contadini, p. 26]

So, liberty is the precondition for the maximum development of one’s individual potential. A healthy, free community will produce free individuals, who in turn will shape the community and enrich the social relationships between the people of whom it is composed. Liberties “do not exist because they have been legally set down on a piece of paper, but only when they have become the ingrown habit of a people, and when any attempt to impair them will meet with the violent resistance of the populace … One compels respect from others when one knows how to defend one’s dignity as a human being. This is not only true in private life; it has always been the same in political life as well.” In fact, we “owe all the political rights and privileges which we enjoy today in greater or lesser measures, not to the good will of their governments, but to their own strength.” [Rudolf Rocker, Anarcho-syndicalism, p. 75]

Direct action is the application of liberty, used to resist oppression in the here and now as well as the means of creating a free society. It creates the necessary individual mentality, the social conditions, and the technical infrastructure in which liberty can flourish.

Liberty for anarchists means a non-authoritarian society in which individuals and groups are free to interact as they wish, and to associate or not. The implications of this are important. First, it implies that an anarchist society will be non-coercive, that is, one in which violence or the threat of violence will not be used to “convince” individuals to do anything. Second, it implies that anarchists are firm supporters of individual sovereignty, and that, because of this support, they also oppose institutions based on coercive authority, i.e. aggression. And finally, it implies that anarchists’ opposition to “government” means only that they oppose centralised, hierarchical, bureaucratic organisations of compulsory government. They do not oppose self-government, through contract, markets, emergent norms, confederations, grassroots organisations, private firms, and so on, as long as these are based on voluntary consent rather than aggression - the initiation or threat of force. Authority is the opposite of liberty; any form of organisation based on political power is a direct threat to the liberty of the people subjected to that power.

I.B.3 - Are anarchists in favor of organisation?

Yes, of course. Without association, a truly human life is impossible. Liberty cannot exist without society and organisation, and prosperity for our current population would be impossible without a division of labor and free trade.

There is no doubt that society needs to be better organised. Presently much of producers' wealth gets plundered by State and redistributed to a small, ruling elite, causing deprivation and suffering for the majority. Because this elite controls the means of coercion through its control of the state (see section II.E), it is able to suppress the the productive class of workers and entrepreneurs and capitalists and ignore the suffering of the underclass.

Many anarchists look to federalism for co-ordinating joint efforts. For anarchism, federalism is the natural complement to self-ownership. With the abolition of the State, society “can, and must, organise itself in a different fashion, but not from top to bottom … The future social organisation must be made solely from the bottom upwards.” [Michael Bakunin: Selected Writings, pp. 205–6]

I.B.4 - Do anarchists favour non-aggression?

Yes, virtually all anarchists hold the non-aggression principle as a fundamental moral belief. (Some frame it as "anti-hierarchy.") The NAP basically says that no one should prevent another from doing any action he is entitled to do. In particular:

The non-aggression principle (NAP) is a moral stance which asserts that aggression is illegitimate.Also called the non-aggression axiom, the anti-coercion principle, the zero aggression principle ZAP, or the non-initiation of force.

Aggression is defined as the initiation or threat of non-consensual physical force against the person or property of another. Aggression is understood to include indirect force such as theft by stealth and fraud. Unlike pacifism, the non-aggression principle does not preclude violence used in self-defense or the defense of others.

Herbert Spencer expressed this as the Law of Equal Freedom. Malatesta concurs, pointing out that anarchism supports “freedom for everybody … with the only limit of the equal freedom for others; which does not mean … that we recognise, and wish to respect, the ‘freedom’ to exploit, to oppress, to command, which is oppression and certainly not freedom.” [Errico Malatesta: His Life and Ideas, p. 53]

I.B.5 - Are anarchists in favour of equality?

No. Anarchists realize that liberty leads to diverse outcomes and natural inequality. Freedom allows natural hierarchies of talent, intelligence, and expertise. The only type of equality that anarchists favor is equality of rights, that is, the equality that humans have in the prerogative to aggress against others - which is none. Herbert Spencer called this "the law of equal freedom."

Each has freedom to do all that he wills provided that he infringes not the equal freedom of any other. — Herbert Spencer, Social Statics, c. 4, § 3The anti-propertarian Chomsky agrees with the propertarian Spencer.

Anarchists do not believe in “equality of endowment,” which is not only non-existent but would be very undesirable if it could be brought about. Everyone is unique. Biologically determined human differences not only exist but are “a cause for joy, not fear or regret.” Why? Because “life among clones would not be worth living, and a sane person will only rejoice that others have abilities that they do not share.”

— Noam Chomsky on Anarchism, Marxism & Hope for the Future, p. 782

Nor are anarchists in favour of so-called “equality of outcome.” We have no desire to live in a society were everyone gets the same goods, lives in the same kind of house, wears the same uniform, etc. Part of the reason for the anarchist revolt against statism is that it standardizes so much of life.

The spirit of authority, law, written and unwritten, tradition and custom force us into a common groove and make a man [or woman] a will-less automation without independence or individuality… All of us are its victims, and only the exceptionally strong succeed in breaking its chains, and that only partly. — What is Anarchism?, p. 165

Equality of outcome can only be introduced and maintained by force, which would not be equality anyway, as some would have more power than others! Equality of outcome is particularly hated by anarchists, as we recognise that every individual has different needs, abilities, desires and interests. To make all the same would be tyranny.

I.B.6 - Why is decentralization important?

Centralization of power favors the State, while decentralization favors freedom and anarchism. Places with pluralist decentralized loci of power are almost always freer than places where power is concentrated. There are several reasons for this. One is simple proximity - we can confront local tyrants, but not far-away rulers defended by armies. Another reason is that one can opt out easier, the more alternatives there are and the more local they are. When "voting with your feet" has near-zero cost, then anarchism will prevail.

Wherever something is wrong, something is too big. If the stars in the sky or the atoms of uranium disintegrate in spontaneous explosion, it is not because their substance has lost its balance. It is because matter has attempted to expand beyond the impassable barriers set to every accumulation. Their mass has become too big. If the human body becomes diseased, it is, as in cancer, because a cell, or a group of cells, has begun to outgrow its allotted narrow limits. And if the body of a people becomes diseased with the fever of aggression, brutzdity, collectivism, or massive idiocy, it is not because it has fallen victim to bad leadership or mental derangement. It is because huma beings, so charming as individuals or in small aggregations, have been welded into overconcentrated social units such as mobs, unions, cartels, or great powers. — Leopold Kohr, The Breakdown of Nations

Anarchists do sometimes have the desire to form “unions” (to use Max Stirner’s term) with other people. These unions, or associations, must be based on mutuality and individuality, i.e. they must be organised in an anarchist manner - voluntarily.

It is not an exaggeration to say that anarchism and radical decentralization are essentially the same thing. Even the minarchist economist Ludwig von Mises sounds like an anarchist when talking about secession:The right of self-determination in regard to the question of membership in a state thus means: whenever the inhabitants of a particular territory, whether it be a single village, a whole district, or a series of adjacent districts, make it known, by a freely conducted plebiscite, that they no longer wish to remain united to the state to which they belong at the time, but wish either to form an independent state or to attach themselves to some other state, their wishes are to be respected and complied with. This is the only feasible and effective way of preventing revolutions and civil and international wars. …

However, the right of self-determination of which we speak is not the right of self-determination of nations, but rather the right of self-determination of the inhabitants of every territory large enough to form an independent administrative unit. If it were in any way possible to grant this right of self-determination to every individual person, it would have to be done. This is impracticable only because of compelling technical considerations, which make it necessary that a region be governed as a single administrative unit and that the right of self-determination be restricted to the will of the majority of the inhabitants of areas large enough to count as territorial units in the administration of the country.

— Ludwig von Mises, from Anarchism and Radical Decentralization Are the Same Thing

I.B.7 - Why do anarchists argue for self-ownership and self-liberation?

Self-ownership is the basis of liberty. If you do not own yourself, then you are a slave. American individualist anarchists, strongly influenced by the abolitionist movement against slavery, called it sovereignty of the individual.

Liberty, then, is the sovereignty of the individual, and never shall man know liberty until each and every individual is acknowledged to be the only legitimate sovereign of his or her person, time, and property, each living and acting at his own cost. — Josiah Warren, Equitable Commerce p 21.

Liberty, by its very nature, cannot be given. An individual cannot be freed by another, but must break his or her own chains through their own effort. Of course, self-effort can also be part of collective action, and in many cases it has to be in order to attain its ends. As Emma Goldman points out:

History tells us that every oppressed class [or group or individual] gained true liberation from its masters by its own efforts. — Red Emma Speaks, p. 167.

This is because anarchists recognise that government systems shape those subject to them. As Bookchin argued, “class societies organise our psychic structures for command or obedience.” This means that people internalise the values of hierarchical and class society and, as such, “the State is not merely a constellation of bureaucratic and coercive instituions. It is also a state of mind, an instilled mentality for ordering reality … Its capacity to rule by brute force has always been limited … Without a high degree of cooperation from even the most victimised classes of society such as chattel slaves and serfs, its authority would eventually dissipate. Awe and apathy in the face of State power are products of social conditioning that renders this very power possible.” [The Ecology of Freedom, p. 159 and pp. 164–5] Self-liberation is the means by which we break down both internal and external chains, freeing ourselves mentally as well as physically.

Anarchists have long argued that people can only free themselves by their own actions. The various methods anarchists suggest to aid this process will be discussed in section I (“What Do Anarchists Do?”) and will not be discussed here. However, these methods all involve people engaging in voluntary actions, acting in ways that empower them, create alternative structures and institutions to the State, which eliminates dependence on rulers to do things for them. Anarchism is based on people acting for themselves to create voluntary alternatives to the State, performing what anarchists call agorism or direct action.

"It's hard to fight an enemy with outposts in your head." —Sally Kempton

Building parallel structures to institutions and activities currently captured by State not only frees people from government rulership, but demonstrates practically how the government is unnecessary. It is following Mahatma Gandhi's advice:

"You must be the change you wish to see in the world."

Unless a process of self-emancipation occurs, a free society is impossible. Only when individuals free themselves, both materially by abolishing the State, and intellectually by freeing themselves of submissive attitudes, can a free society be achieved. We should never forget that State power, to a great extent, is power over the minds of docile subjects.

Étienne de la Boétie, the pioneer of mass civil disobedience who influenced both Tolstoy and Gandhi, said it well:

"From all these indignities, such as the very beasts of the field would not endure, you can deliver yourselves if you try, not by taking action, but merely by willing to be free. Resolve to serve no more, and you are at once freed. I do not ask that you place hands upon the tyrant to topple him over, but simply that you support him no longer; then you will behold him, like a great Colossus whose pedestal has been pulled away, fall of his own weight and break into pieces." — Étienne de la Boétie, The Politics of Obedience: The Discourse on Voluntary Servitude (1548).

"From all these indignities, such as the very beasts of the field would not endure, you can deliver yourselves if you try, not by taking action, but merely by willing to be free. Resolve to serve no more, and you are at once freed. I do not ask that you place hands upon the tyrant to topple him over, but simply that you support him no longer; then you will behold him, like a great Colossus whose pedestal has been pulled away, fall of his own weight and break into pieces." — Étienne de la Boétie, The Politics of Obedience: The Discourse on Voluntary Servitude (1548).

I.B.8 - Do anarchists oppose hierarchy?

No, not as such. We have seen how anarchists abhor authoritarianism, which we operationalize as aggression, but not all hierarchical institutions involve force. Some hierarchies are voluntary and consensual, a teacher and student for example. Thus anarchists are not against hierarchy as such, but we are against coercive hierarchies, that is, hierarchies based on aggression.

It is unfortunate that some anarchists have become distracted by the fuzzy term "hierarchy," and attempt to explain anarchist ideas on that unsound basis. Early anarchists rarely used the term "hierarchy," and when they did they were talking about government (or sometimes church) hierarchy, not hierarchy as such. The pioneers of anarchism used "authority" quite a bit, but not "hierarchy." Since "hierarchy" obscures the point - non-aggression and non-rulership - it is best that the term be avoided. If some government act can be explained using hierarchy, then it can be better explained using aggression.

I.B.9 - Do anarchists oppose property?

No. On the contrary virtually all anarchists support some kind of resource usage norms, aka property. Pierre Proudhon described two types of property in his famous tract "What is Property?".

1. Property pure and simple, the dominant and seigniorial power over a thing; or, as they term it, naked property.

2. Possession.

“Possession,” says Duranton, “is a matter of fact, not of right.”Toullier: “Property is a right, a legal power; possession is a fact.”

The tenant, the farmer, the commanditè, the usufructuary, are possessors; the owner who lets and lends for use, the heir who is to come into possession on the death of a usufructuary, are proprietors. If I may venture the comparison: a lover is a possessor, a husband is a proprietor.

— Pierre Proudhon, What is Property? Ch. 2In addition to sticky ("naked") property and possession property norms, there is also the collectivist property norms of anarcho-socialists. All three are property systems, in the sense of resource usage norms.

Why do some self-labeled anarchists say they oppose property? Because they use the term "property" in a rather outdated Marxian manner, to mean only sticky property, or in some cases, only capital goods held as sticky property. In short, this is socialist jargon - non-standard terminology. If one uses the standard modern definition of property - a set of resource usage norms - then all anarchists support property.

Another source of confusion comes from a shallow misunderstanding of Proudhon. People who know only that Proudhon wrote "Property is theft" are ignorant that he also wrote "Property is liberty" and "Property is impossible." A deeper understanding of Proudhon shows us that Proudhon was against decreed property - an attitude common to all anarchists - but he admitted the usefulness of possession property and private property in general (including sticky property) since it created a counter-power against the State.

Property — absolute, uncontrollable — protects itself. It is the defensive weapon of the citizen, his shield; labour is his sword. — Pierre Proudhon, The Theory of Property

Then there is disinformation put out by some anarcho-socialists, falsely asserting that all anarchists are socialist. This is petty sectarianism, basically a "one true Scotsman" fallacy. Anarchists can favor any property system consistent with statelessness.

I.B.10 - What sort of society do anarchists want?

Anarchists desire a decentralised society, based on free association. We consider this form of society the best one for maximising the value we have outlined above - liberty. Only by a rational decentralisation of power, both structurally and territorially, can individual liberty be fostered and encouraged. The delegation of political power, the power to rule, into the hands of a minority is an obvious denial of individual liberty and dignity. Rather than taking the management of their own affairs away from people and putting it in the hands of others, anarchists favour organisations which minimise authority, using voluntary economic power rather than coercive political power.

Free association is the cornerstone of an anarchist society. Individuals must be free to join together as they see fit, and disassociate as they see fit. This is the basis of freedom and human dignity. Both compulsory integration and compulsory segregation are forms of rulership.

As can be seen, anarchists wish to create a society based upon structures that ensure that no individual or group is able to aggress against others. Anarchy, however, is not some distant goal but rather an aspect of current struggles against oppression. Means and ends are linked. Anarchists try to create the kind of world we want in our current struggles, and do not think our ideas are only applicable in a future stateless society.

For a fuller discussion on what an anarchist society would look like, see section VI.

I.B.11 - What will abolishing the State achieve?

The creation of a new society based upon voluntary association will have an incalculable effect on everyday life. The empowerment of millions of people will transform society in ways we can only guess at now. Here are some of them.

- The end of organized mass murder funded by legalized plunder.

- The end of State nationalization of industries - statist socialism.

- The end of State favoritism and collaboration with special interests - corporatism.

- No government plunder of your wealth!

- No government imprisonment for "victimless crimes."

- No government licensure or other coercive barriers to production.

- Choice in legal systems, property systems, education methods, and lifestyles.

I.B.12 - Do anarchists favor democracy or contract?

Some favor democracy, while others favor contract and emergent "market" solutions. The latter often look down on "winner take all" democracy as a type of rulership.Anarchists favor voluntary means, and there are two basic ways to do this: by contract and by voting. The former sees free markets and voluntary contracts as the basis of social order, while the latter favors committees and decentralized democracy and (hopefully) consensus. Collectivist anarchists tend to favor voting, while individualist anarchists tend to favor contract. Both strategies have their pros and cons.

| Democracy vs. Autonomy | Democratic | Consensual |

|---|---|---|

| stability | lower | higher |

| flexibility | higher | lower |

| property protection | lower | higher |

| solidarity | higher | lower |

| distributive bias | end-state (fairness, equality) |

entitlement (justice, merit) |

Anarcho-capitalists and most mutualists prefer contract wherever possible. Proudhon wrote:

In place of laws, we will put contracts. No more laws voted by a majority, nor even unanimously; each citizen, each town, each industrial union, makes its own laws.

— The General Idea of the Revolution, pp. 245–6]

Anarcho-socialists look to federalism to ensure that decisions flow from the bottom-up. Of course it could be argued that if you are in a minority, you are governed by others (“Democratic rule is still rule” [L. Susan Brown, The Politics of Individualism, p. 53]). Now, the concept of direct democracy as we have described it is not necessarily tied to the concept of majority rule. If someone finds themselves in a minority on a particular vote, he or she is confronted with the choice of either consenting, refusing to recognise it as binding, or opting out.

As the minority has the right to secede from the association as well as having extensive rights of action, protest and appeal, majority rule is not imposed as a principle. Rather, it is purely a decision making tool which allows minority dissent and opinion to be expressed (and acted upon) while ensuring that no minority forces its will on the majority. In other words, majority decisions are not binding on the minority. After all, as Malatesta argued:

One cannot expect, or even wish, that someone who is firmly convinced that the course taken by the majority leads to disaster, should sacrifice his [or her] own convictions and passively look on, or even worse, should support a policy he [or she] considers wrong. — Errico Malatesta: His Life and Ideas, p. 132

Freedom of contract and trade is a sort of hyper-democracy. Instead of winner-take-all, however, each participant in a market gets what he "voted" for with his money. I can drink Becks even if the majority prefer Budweiser. Or conversely: In a democracy, everyone would have to drink Bud.

“While liberals are in favor of any sexual activity engaged in by two consenting adults, when these consenting adults engage in trade or exchange, the liberals step in to harass, cripple, restrict, or prohibit that trade. And yet both the consenting sexual activity and the trade are similar expressions of liberty in action.” — Murray N. Rothbard, A Future of Peace and CapitalismA freed market is anarchism in action. People make their own decisions and bear the benefits and costs. No one should prevent capitalist acts between consenting adults.

The free market is not a system. It is not a policy dictated by anyone in particular. It is not something that Washington implements. It does not exist in any legislation, law, bill, regulation, or book. It is what you get when people act on their own, entirely without central direction, and with their own property, and within human associations of their own creation and in their own interest. It is the beauty that emerges in absence of control. — Jeffery Tucker, Bitcoin is not a monetary system

Jeffery Tucker

I.B.13 - Are anarchists individualists or collectivists?

Anarchists can be either. Any property system or norm set consistent with statelessness is compatible with anarchism. But as a matter of fact, most anarchists identify with either collectivist anarchism (anarcho-socialism) or individualist anarchism, which includes mutualism and anarcho-capitalism. The "schools" of anarchism from an economic standpoint range from extreme anti-propertarianism to full-fledged non-proviso Lockean "sticky" property.

For anarchists, the idea that individuals should sacrifice themselves for the “group” or “greater good” is nonsensical. Groups are made up of individuals, and if people think only of what’s best for the group, the group will be a lifeless shell. It is only the dynamics of human interaction within groups which give them life. “Groups” cannot think, only individuals can. This idea is called methodological individualism.

Ironically, authoritarian “collectivists” often fall into a most particular kind of “individualism,” namely the “cult of the personality” and leader worship. This is to be expected, since such collectivism lumps individuals into abstract groups, denies their individuality, and ends up with the need for someone with enough individuality to make decisions — a problem that is “solved” by the leader principle. Stalinism and Nazism are excellent examples of this phenomenon.

Therefore, anarchists recognise that individuals are the basic unit of society and that only individuals have interests and feelings. This means they oppose “collectivism” and the glorification of the group. In anarchist theory the group exists only to aid and develop the individuals involved in them. So while society and the groups they join shapes an individual, the individual is the true basis of society.

Of course, propertarianism and methodological individualism should not be confused with insularity or the mistaken notion that 'man is an island' who should shun cooperation with others. Groups and associations are an essential aspect of individual life. Indeed, without a worldwide division of labor most people on earth would starve, or at least have a much lower standard of living. Collectivism, with its implicit suppression of the individual, ultimately impoverishes the community, as groups are only given life by the individuals who comprise them.

I.B.14 - What about “human nature”?

Anarchists, far from ignoring “human nature,” have the only political theory that gives this concept deep thought and reflection. Too often, “human nature” is flung up as the last line of defence in an argument against anarchism, because it is erroneously believed that anarchism assumes people are good. But anarchists have no such belief, at least as anarchists, although there no doubt exist a few utopian anarchists who do. Hence Chomsky:

Individuals are certainly capable of evil … But individuals are capable of all sorts of things. Human nature has lots of ways of realising itself, humans have lots of capacities and options. Which ones reveal themselves depends to a large extent on the institutional structures. If we had institutions which permitted pathological killers free rein, they’d be running the place. The only way to survive would be to let those elements of your nature manifest themselves. — Noam Chomsky in debate with Michel Foucault (1971)

The vast majority of anarchists hold the reasonable belief that people are neither all angels, nor all devils. People tend to act reasonably non-aggressive, except for a few psychopaths. But let's take all three possibilities for completeness. Anarchists believe:

Anarchism is better than statism regardless of how good or bad man is.

- If man is good, then the State is unnecessary.

- If man is bad, then States run by men only amplify the bad.

- Most anarchists consider some men to be generally okay, but with some bad, and consider how to deal with this realistic situation. Anarchists contend that monopoly courts (and police) are not the answer.

I.B.15 - Do anarchists support terrorism?

No, for four reasons.

- Terrorism means either targeting or not worrying about killing innocent people. One does not convince people of one’s ideas by blowing them up. Killing innocent people violates the NAP - the non-aggression presumption/principle.

- Anarchism is about self-liberation. One cannot blow up a social relationship. Freedom cannot be created by the actions of an elite few destroying rulers on behalf of the majority. Simply put, a “structure based on centuries of history cannot be destroyed with a few kilos of explosives.” [Kropotkin, quoted by Martin A. Millar, Kropotkin, p. 174] So long as people feel the need for rulers, governments will exist. Freedom cannot be given, only taken.

- Means determine the ends and terrorism by its very nature violates life and liberty of individuals and so cannot be used to create an anarchist society. The history of, say, the Russian Revolution, confirmed Kropotkin’s insight that “[v]ery sad would be the future revolution if it could only triumph by terror.” [quoted by Millar, Op. Cit., p. 175]

- Terrorism is almost always tactically wrong, since the government has more fire-power than you.

When it gets down to having to use violence, then you are playing the system’s game. The establishment will irritate you – pull your beard, flick your face – to make you fight. Because once they’ve got you violent, then they know how to handle you. The only thing they don’t know how to handle is non-violence and humor. — John Lennon

When it gets down to having to use violence, then you are playing the system’s game. The establishment will irritate you – pull your beard, flick your face – to make you fight. Because once they’ve got you violent, then they know how to handle you. The only thing they don’t know how to handle is non-violence and humor. — John Lennon

How is it, then, that anarchism is associated with violence? Partly this is because the state and media insist on referring to terrorists who are not anarchists as anarchists. For example, the German Baader-Meinhoff gang were often called “anarchists” despite their self-proclaimed Marxist-Leninism. Smears, unfortunately, work.

The main historical reason for the association of terrorism with anarchism is the “propaganda by the deed” period — roughly from 1880 to 1900. This was marked by a small number of anarchists assassinating members of the ruling class (royalty, politicians and so forth). At its worse, this period saw theatres and shops frequented by members of the bourgeoisie targeted. Propaganda by the deed began in France after the 20,000-plus deaths due to the French state’s brutal suppression of the Paris Commune, in which many anarchists were killed.

Max Stirner

Downplaying of statist violence is hardly surprising. “The State’s behaviour is violence,” points out Max Stirner, “and it calls its violence ‘law;’ that of the individual, ‘crime.’” [The Ego and Its Own, p. 197] Little wonder, then, that anarchist violence is condemned but the repression (and often worse violence) that provoked it ignored and forgotten. Anarchists point to the hypocrisy of the accusation that anarchists are “violent” given that such claims come from either supporters of government or the actual governments themselves, governments “which came into being through violence, which maintain themselves in power through violence, and which use violence constantly to keep down rebellion and to bully other nations.” [Howard Zinn, The Zinn Reader, p. 652]

It must be noted that most 19th century anarchists did not support terrorism. Benjamin Tucker and virtually all American Individualist anarchists condemned terrorist "propaganda of the deed" tactics.

I.B.16 - What ethical views do anarchists hold?

Anarchist viewpoints on ethics vary considerably, although all share a common belief in the need for an individual to develop within themselves their own sense of ethics. All anarchists agree with Max Stirner that an individual must free themselves from the confines of existing morality and question that morality — “I decide whether it is the right thing for me; there is no right outside me.” [The Ego and Its Own, p. 189] Few anarchists, however, would go so far as Stirner and reject any concept of ethics at all. Such amoralism is considered worse than a mistaken or wrong morality, to most anarchists.

Many if not most anarchists hold some form of the NAP. For some non-aggression is a heuristic, for others a default position such that deviance should be justified (Michael Huemer), others as a principle to be observed except in "lifeboat emergencies," and others as an absolute moral imperative. This non-aggression principle has a long history.

Being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions.

— John Locke, Second Treatise on Government

The precondition of a civilized society is the barring of physical force from social relationships. … In a civilized society, force may be used only in retaliation and only against those who initiate its use.

— Ayn Rand, Man's Rights

No one may threaten or commit violence ('aggress') against another man's person or property. Violence may be employed only against the man who commits such violence; that is, only defensively against the aggressive violence of another. In short, no violence may be employed against a nonaggressor. Here is the fundamental rule from which can be deduced the entire corpus of libertarian theory.. — Murray Rothbard, War, Peace, and the State

Any system of ethics which is not based on individual jurisdiction and moral autonomy can only be authoritarian. Erich Fromm explains why:

Formally, authoritarian ethics denies man’s capacity to know what is good or bad; the norm giver is always an authority transcending the individual. Such a system is based not on reason and knowledge but on awe of the authority and on the subject’s feeling of weakness and dependence; the surrender of decision making to the authority results from the latter’s magic power; its decisions can not and must not be questioned. Materially, or according to content, authoritarian ethics answers the question of what is good or bad primarily in terms of the interests of the authority, not the interests of the subject; it is exploitative, although the subject may derive considerable benefits, psychic or material, from it. — Erich Fromm. Man For Himself, p. 10

Moral autonomy is essential to liberty. Philosopher Robert Wolff sums up autonomy as the ethical justification of anarchism:

The defining mark of the state is authority, the right to rule. The primary obligation of man is autonomy, the refusal to be ruled. It would seem, then, that there can be no resolution of the conflict between the autonomy of the individual and the putative authority of the state. Insofar as a man fulfills his obligation to make himself the author of his decisions, he will resist the state's claim to have authority over him. That is to say, he will deny that he has a duty to obey the laws of this state simply because they are the laws. In that sense, it would seem that anarchism is the only political doctrine consistent with the virtue of autonomy. — Robert Paul Wolff, In Defense of Anarchism

I.B.17 - Why are most anarchists atheists?

Anarchy … is the only logical outcome of freethought - the ripened fruit of which freethinking is the potent seed. — Voltairine de Cleyre, A Lance for Anarchy (1891)

It is a fact that most anarchists are atheists. They reject the idea of god and oppose all forms of religion, particularly organised religion. Today, in secularised western European countries, religion has lost its once dominant place in society. This often makes the militant atheism of anarchism seem strange. However, once the negative role of religion is understood the importance of libertarian atheism becomes obvious. It is because of the role of religion and its institutions that anarchists have spent some time refuting the idea of religion as well as propagandising against it.

So why do so many anarchists embrace atheism? The simplest answer is that most anarchists are atheists because it is a logical extension of anarchist ideas. If anarchism is the rejection of illegitimate authorities, then it follows that it is the rejection of the so-called Ultimate Authority, God. Anarchism is grounded in reason, logic, and scientific thinking, not religious thinking. Anarchists tend to be sceptics, and not believers. Most anarchists consider the Church to be steeped in hypocrisy and the Bible a work of fiction, riddled with contradictions, absurdities and horrors. It is notorious in its debasement of women and its sexism is infamous. Yet men are treated little better. Nowhere in the bible is there an acknowledgement that human beings have inherent rights to life, liberty, happiness, dignity, fairness, or self-government. In the bible, humans are sinners, worms, and slaves (figuratively and literally, as it condones slavery). God has all the rights, humanity is nothing.

This is unsurprisingly, given the nature of religion. Bakunin put it best:

The idea of God implies the abdication of human reason and justice; it is the most decisive negation of human liberty, and necessarily ends in the enslavement of mankind, both in theory and in practice.Unless, then, we desire the enslavement and degradation of mankind … we may not, must not make the slightest concession either to the God of theology or to the God of metaphysics. He who, in this mystical alphabet, begins with A will inevitably end with Z; he who desires to worship God must harbour no childish illusions about the matter, but bravely renounce his liberty and humanity.

If God is, man is a slave; now, man can and must be free; then, God does not exist.

— Michael Bakunin, God and the State, p. 25]

For most anarchists, then, atheism is required due to the nature of religion. Anarchists argue that we must do without the harmful myth of god and all it entails. Religion has other, more practical, problems with it from an anarchist point of view.

Firstly, religions have been a source of inequality and oppression. Christianity (like Islam), for example, has always been a force for repression whenever it holds any political or social sway - believing you have a direct line to god is a sure way of creating an authoritarian society. The Church has been a force of social repression, genocide, and the justification for every tyrant for nearly two millennia - the infamous coalition of Church and State. The Bible says, “By their fruits shall ye know them.” We anarchists agree, but unlike the church we apply this truth to religion as well.

Secondly, religion conditions the oppressed to humbly accept their place in life by urging the oppressed to be meek and await their reward in heaven. As Emma Goldman argued, Christianity (like religion in general) “contains nothing dangerous to the regime of authority and wealth; it stands for self-denial and self-abnegation, for penance and regret, and is absolutely inert in the face of every [in]dignity, every outrage imposed upon mankind.” [Red Emma Speaks, p. 234]

Thirdly, religion has always been a conservative force in society. This is unsurprising, as it bases itself not on investigation and analysis of the real world but rather in repeating the truths handed down from above and contained in a few holy books.

"May the last king be strangled in the guts of the last priest."

- Jean Meslier and Denis Diderot

That said, anarchists do not deny that religions contain important ethical ideas or truths. Moreover, religions can be the base for strong and loving communities and groups. They can offer a sanctuary from the alienation and oppression of everyday life and offer a guide to action in a world where everything is for sale. Many aspects of, say, Jesus’ or Buddha’s life and teachings are inspiring and worth following. If this were not the case, if religions were simply a tool of the powerful, they would have long ago been rejected. Rather, they have a dual-nature in that contain both ideas necessary to live a good life as well as apologetics for power. If they did not, the oppressed would not believe and the powerful would suppress them as dangerous heresies.

It should be stressed that anarchists, while overwhelmingly hostile to the idea of the Church and an established religion, do not object to people practising religious belief on their own or in groups, so long as that practice doesn’t impinge on the liberties of others. For example, a cult that required human sacrifice or slavery would be antithetical to anarchist ideas, and would be opposed. But peaceful systems of belief could exist in harmony within in anarchist society. The anarchist view is that religion is a personal matter, above all else — if people want to believe in something, that’s their business, and nobody else’s as long as they do not impose those ideas on others. All we can do is discuss their ideas and try and convince them of their errors.

To end, it should noted that we are not suggesting that atheism is somehow mandatory for an anarchist. Far from it. As we see in the next section, there are anarchists who do believe in god or some form of religion. For example, Tolstoy combined libertarian ideas with a devote Christian belief. His ideas, along with Proudhon’s, influences the Catholic Worker organisation, founded by anarchists Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin in 1933 and still active today.

I.C - What types of anarchism are there?

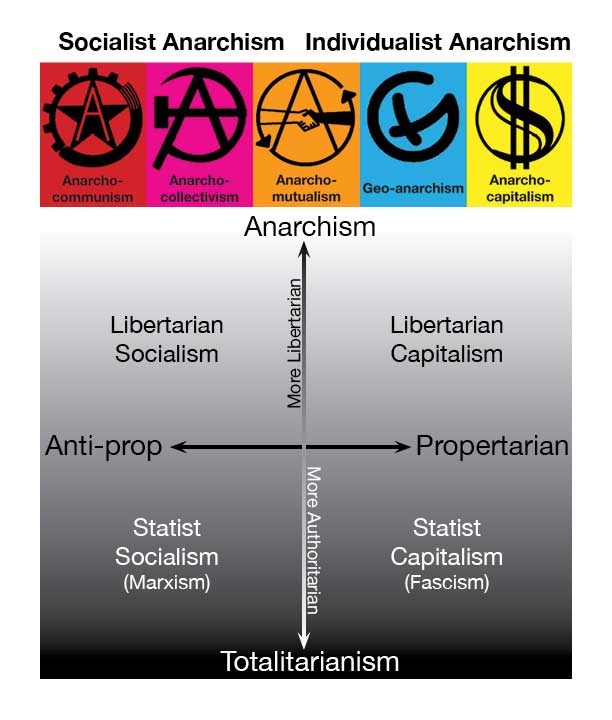

One thing that soon becomes clear to any one interested in anarchism is that there is not one single form of anarchism. Rather, there are different schools of anarchist thought, different types of anarchism which have many disagreements with each other on numerous issues. These types are usually distinguished by their particular conception of authority. More specifically, schools of anarchism differ on 1) preferred economic and property arrangements, 2) tactics, and/or 3) goals, i.e. their vision of a free society.

The most important and internally controversial division concerns the economic arrangements most suitable to human freedom. Beware of sectarians, who claim that only their favorite "flavor" of economics is "true anarchism." Benjamin Tucker clues us in:

Anarchism is for liberty, and neither for nor against anything else. … A Socialist may or may not be an Anarchist, and an Anarchist may or may not be a Socialist. Relaxing scientific exactness, it may be said, briefly and broadly, that Socialism is a battle with usury and that Anarchism is a battle with authority. — Benjamin Tucker, Armies that Overlap, Instead of a Book.

The main differences are between “individualist” and “social” anarchists, or anarcho-socialists. Of the two, anarcho-socialists (communist-anarchists, anarcho-syndicalists and so on) were the vast majority until the 21st century, when anarcho-capitalism became dominant. In this section we indicate the differences between these main trends within the anarchist movement. As will soon become clear, they disagree on the nature of a free society (and how to get there). In a nutshell, anarcho-socialists prefer communal solutions and "democracy" to social problems, while individualist anarchists prefer individual or contractual solutions and have a more individualistic vision of the good society. The most significant difference is in their respective preferred property systems: anarcho-socialists want some sort of collective property, while individualists want some sort of private property.

In addition to this major disagreement, anarchists also disagree over such issues as syndicalism, pacifism, “lifestylism,” animal rights and a whole host of other ideas, but these, while important, are only different aspects of anarchism. Beyond a few key ideas, the anarchist movement (like life itself) is in a constant state of change, discussion and thought — as would be expected in a movement that values freedom so highly.

Anarchist ideas have developed in many different situations and, consequently, have reflected those circumstances. Individualist anarchism initially developed in pre-industrial America, and as a result has a different perspective on many issues than anarcho-socialism. America had wilderness and homesteading, while European anarchism was concerned with land enclosure, remnants of feudalism, and the ancien regime. Entrepreneurship and experimentation was stressed in America, while class struggles and aristocracy were European concerns. Of course, immigration cross-pollinated these anarchisms.

I.C.1 - What are the differences between individualist and socialist anarchists?

While there is a tendency for individuals in both camps to claim that the proposals of the other camp would lead to the creation of some kind of state, this is an exaggeration. The differences between individualists and anarcho-socialists are significant, but in a stateless society it would be entirely possible for various economic systems to coexist. Both forms of anarchism are anti-state by definition, and both favor decentralization, pluralism, and consent. The major difference, as noted, is in resource usage norms, aka property systems.

Definitions

- property

- A socially recognized relationship between a person (or group) and a scarce entity regarding disposition and control. Also "property" used to refer to the scarce entity in this relationship. "Owner" is used to refer to the person or group. sticky property - a property relationship characterized by private jurisdiction, homesteading, ownership lasting until consensual transfer, with no restrictions on who may own.

- sticky property

- a property relationship characterized by private jurisdiction, homesteading, ownership lasting until consensual transfer, with no restrictions on who may own.

- possession property (aka usufruct)

- a property relationship characterized by private jurisdiction, homesteading, lasting only while continuous use or occupation is maintained, with no restrictions on who may own.

- collective property

- a property relationship characterized by group, class, or caste jurisdiction, with limited power to transfer, and significant restrictions on who may own what, especially capital goods aka the means of production.

In the diagram above, propertarianism - support for private property - is on the right and opposition to private property is on the left. Thus, anarcho-capitalism is on the far right, geoism and mutualism with their modified forms of private property in the middle, and anarcho-collectivism and anarcho-communism are on the far left, being strongly against private property due to their exploitation theory. Mutualism is in the middle, with some mutualists, like Benjamin Tucker, capitalist in all but value theory, and others giving Proudhon's writings a distinct socialist anti-propertarian slant. Mutualists do favor free markets, like other individualists. Today, Kevin Carson is the most well-known proponent of mutualism.

Besides property norms, there are two other differences between individualists and collectivists. The first is in regard to the means of action in the here and now (and so the manner in which anarchy will come about). Individualists generally prefer evolutionary means, realizing that there will be revolutionary advances at times. They give priority to education and the creation of alternative institutions, such as alternative currencies, neighborhood arbitration and defense groups, and untaxed markets. They might support anti-war or justice-related protests and other non-violent forms of resistance or moral suasion, such as boycott and the non-payment of taxes.

While most anarcho-socialists recognise the need for education and to create alternative structures, most do not believe that this is enough to attain anarchy. They do not ignore the importance of reforms that increase libertarian tendencies, they believe revolutionary violence will be necessary to kill the State. In short, anarcho-socialists are mainly revolutionists rather than evolutionists. However, since some anarcho-socialists are purely evolutionist, this difference is not the most important one dividing anarcho-socialists from individualists.

The second major difference concerns the form of anarchist economy proposed. Individualists prefer a market-based system of distribution while anarcho-socialists favor a need-based system. Both agree that the current system of State decreed property "rights" must be abolished and that entitled rights must replace decreed rights. Of course, as noted above, anarchists disagree on what the best entitled rights - resource usage norms - are. Thus, in a free society we expect property panarchy - a diverse pluralist patchwork of property experiments.

The anarcho-socialist generally argues for communal ownership and use. This would involve collective ownership of the means of production and distribution, with personal possessions remaining for things you use, but not what was used to create them. Thus “your watch is your own, but the watch factory belongs to the people.” “Actual use,” continues Berkman, “will be considered the only title — not to ownership but to possession. The organisation of the coal miners, for example, will be in charge of the coal mines, not as owners but as the operating agency … Collective possession, co-operatively managed in the interests of the community, will take the place of personal ownership privately conducted for profit.” [What is Anarchism?, p. 217]

Individualists, on the other hand, prefer private ownership and voluntary association, without any restriction on who can own capital goods. Collective ownership not only has the problem of acquiring capital goods, but also the calculation problem that Mises pointed out long ago - that non-market systems cannot calculate the relative scarcity of production factors, making it hard to plan rationally. (See II.F.2 for more about this.) Fortunately for socialists, nearby individualist communities and producers create the necessary price information. We have the seeming irony that market anarchism makes anarcho-socialism possible!